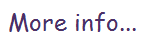

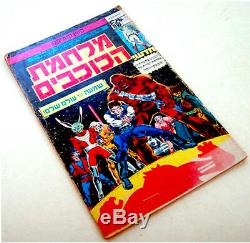

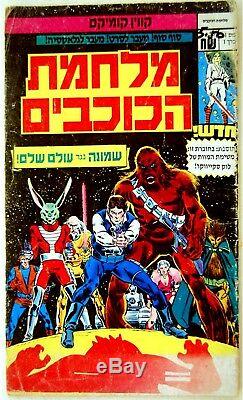

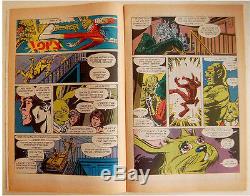

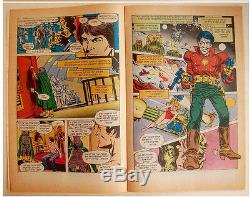

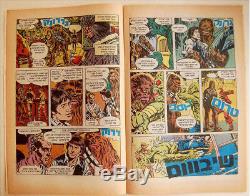

Original 1977 No. 1 Israel STAR WARS Comics CHAYKIN Roy Thomas LUKASFILM Hebrew

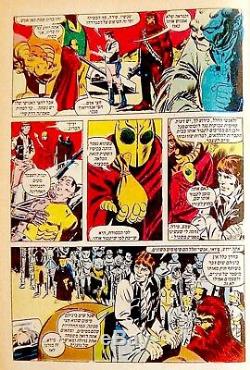

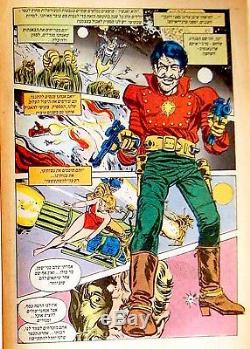

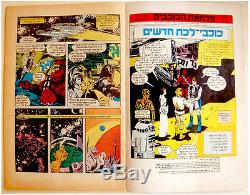

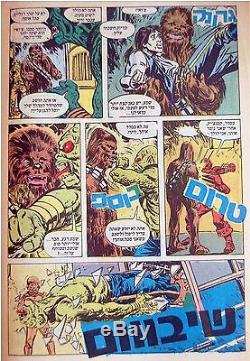

It took the Hebrew publishers almost 10 years to obtain the rights and in 1986 this fascinating HEBREW EDITION was published in ISRAEL in the HEBREW language , Being read and printed from right to left (Being actualy a mirror image of the original English version). Around 7 x 10.5. Unused but suffers from slight shelf wear.

Shot mostly in Tunisia, England, and Guatemala, the film was met with numerous problems during production, including bad weather conditions, malfunctioning equipment, and financial difficulties. The script underwent numerous changes, and Lucas founded Industrial Light & Magic specifically to create the groundbreaking visual effects needed for the film.

Star Wars was released theatrically in the United States on May 25, 1977. It surpassed Jaws (1975) to become the highest-grossing film of all time until E. When adjusted for inflation as of 2013, Star Wars was the second-highest-grossing film in the United States and Canada, and the third-highest-grossing film in the world. It received 10 Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture), winning seven.The droids are captured by Jawa traders, who sell the pair to moisture farmers Owen and Beru Lars and their nephew, Luke Skywalker. While he cleans R2-D2 Luke accidentally triggers the playing of part of Leia's recording, in which she requests help from Obi-Wan Kenobi.

Luke wonders if she is referring to Ben Kenobi, a hermit who lives nearby; then he retires for the evening. The next morning Luke finds R2-D2 searching for Obi-Wan, and meets Ben, who reveals himself to be Obi-Wan. Obi-Wan tells Luke of his days as a Jedi, who were a faction of former galactic peacekeepers with supernatural powers derived from an energy field called the Force, and who were conquered by the Empire. Contrary to his uncle's assertions, Luke learns that his father fought alongside Obi-Wan as a Jedi Knight before he was betrayed and killed by Vader, Obi-Wan's former pupil who turned to the dark side of the Force. Obi-Wan then offers Luke his father's lightsaber. Obi-Wan views Leia's complete message, in which she begs him to take the Death Star plans to her home planet of Alderaan and give them to her father for analysis. Obi-Wan invites Luke to accompany him to Alderaan and become a student of the Force. Luke initially declines, but, after discovering that Imperial stormtroopers searching for C-3PO and R2-D2 have destroyed his home and killed his aunt and uncle, changes his mind.Cast From left: Luke Skywalker (Mark Hamill), Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher), and Han Solo (Harrison Ford) Anthony Daniels (pictured here in 2005) was convinced to take the role of the droid C-3PO after seeing a design drawing of the character's face Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker: a young man raised by his aunt and uncle on Tatooine, who dreams of something more than his current life Lucas favored casting young actors who lacked long experience. To play Luke (then known as Luke Starkiller), Lucas sought actors who could project intelligence and integrity. While reading for the character, Hamill found the dialogue to be extremely odd because of its universe-embedded concepts.

" George Lucas[25] Since commencing his writing process in January 1973, Lucas had done "various rewrites in the evenings after the day's work. " He would write four different screenplays for Star Wars, "searching for just the right ingredients, characters and storyline.

It's always been what you might call a good idea in search of a story. [26] By May 1974, he had expanded the film treatment into a rough draft screenplay, adding elements such as the Sith, the Death Star, and a general by the name of Annikin Starkiller. He changed Starkiller to an adolescent boy, and he shifted the general into a supporting role as a member of a family of dwarfs. [10][22] Lucas envisioned the Corellian smuggler, Han Solo, as a large, green-skinned monster with gills. He based Chewbacca on his Alaskan Malamute dog, Indiana (whom he would later use as namesake for his character Indiana Jones), who often acted as the director's "co-pilot" by sitting in the passenger seat of his car.The script became more of a fairy tale quest as opposed to the action-adventure of the previous versions. This version ended with another text crawl, previewing the next story in the series. This draft was also the first to introduce the concept of a Jedi turning to the dark side: the draft included a historical Jedi who became the first to ever fall to the dark side, and then trained the Sith to use it.

And request the sequel rights to the film. For Lucas, this deal protected Star Wars' unwritten segments and most of the merchandising profits. [10] Lucas finished writing his script in March 1976, when the crew started filming.

He said, What finally emerged through the many drafts of the script has obviously been influenced by science-fiction and action-adventure I've read and seen. And I've seen a lot of it. I'm trying to make a classic sort of genre picture, a classic space fantasy in which all the influences are working together. There are certain traditional aspects of the genre I wanted to keep and help perpetuate in Star Wars."[48] Lucas described a "used future concept to the production designers in which all devices, ships, and buildings looked aged and dirty. [10][49][50] Instead of following the traditional sleekness and futuristic architecture of science fiction films that came before, the Star Wars sets were designed to look inhabited and used. Barry said that the director wants to make it look like its shot on location on your average everyday Death Star or Mos Eisly Spaceport or local cantina. " Lucas believed that "what is required for true credibility is a used future", opposing the interpretation of "future in most futurist movies" that "always looks new and clean and shiny. "[47] Christian supported Lucas's vision, saying "All science fiction before was very plastic and stupid uniforms and Flash Gordon stuff.

George was going right against that. [48] The designers started working with the director before Star Wars was approved by 20th Century Fox. Although Lucas initially provided funds using his earnings from American Graffiti, it was inadequate. As they could not afford to dress the sets, Christian was forced to use unconventional methods and materials to achieve the desired look. He suggested that Lucas use scrap in making the dressings, and the director agreed.

[48] Christian said, I've always had this idea. I used to do it with models when I was a kid. I'd stick things on them and we'd make things look old. [51] Barry, Christian, and their team began designing the props and sets at Elstree Studios. [47] According to Christian, the Millennium Falcon set was the most difficult to build. Christian wanted the interior of the Falcon to look like that of a submarine. [48] He found scrap airplane metal "that no one wanted in those days and bought them". [51] He began his creation process by breaking down jet engines into scrap pieces, giving him the chance to "stick it in the sets in specific ways". [48] It took him several weeks to finish the chess set (which he described as "the most encrusted set") in the hold of the Falcon. The garbage compactor set "was also pretty hard, because I knew I had actors in there and the walls had to come in, and they had to be in dirty water and I had to get stuff that would be light enough so it wouldn't hurt them but also not bobbing around". [48] A total of 30 sets consisting of planets, starships, caves, control rooms, cantinas, and the Death Star corridors were created; all of the nine sound stages at Elstree were used to accommodate them. The massive rebel hangar set was housed at a second sound stage at Shepperton Studios; the stage is the largest in Europe. [47] Filming In 1975, Lucas formed his own visual effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) after discovering that 20th Century Fox's visual effects department had been disbanded. ILM began its work on Star Wars in a warehouse in Van Nuys, California. Most of the visual effects used pioneering digital motion control photography developed by John Dykstra and his team, which created the illusion of size by employing small models and slowly moving cameras. [10] George Lucas tried "to get a cohesive reality" for his feature.[58] Tikal, Guatemala, which served as the setting of the rebel base. The moon Yavin 4, which acted as the rebel base in the film, was filmed in the Mayan temples at Tikal, Guatemala. Lucas selected the location as a potential filming site after seeing a poster of it hanging at a travel agency while he was filming in England. This inspired him to send a film crew to Guatemala in March 1977 to shoot scenes. While filming in Tikal, the crew paid locals with a six pack of beer to watch over the camera equipment for several days.

But some actors really need a lot of pampering and a lot of feedback, and if they don't get it, they get paranoid that they might not be doing a good job. " Kurtz has said that Lucas "wasn't gregarious, he's very much a loner and very shy, so he didn't like large groups of people, he didn't like working with a large crew, he didn't like working with a lot of actors.

[34] Ladd offered Lucas some of the only support from the studio; he dealt with scrutiny from board members over the rising budget and complex screenplay drafts. Then, it was obvious that 8 million wasn't going to do itthey had approved 8 million. " After requests from the team that "it had to be more", the executives "got a bit scared. [34] For two weeks, Lucas and his crew "didn't really do anything except kind of pull together new budget figures". At the same time, after production fell behind schedule, Ladd told Lucas he had to finish production within a week or he would be forced to shut down production. Kurtz said that it came out to be like 9.8 or. 9 or something like that, and in the end they just said,'Yes, that's okay, we'll go ahead. [34] The crew split into three units, with those units led by Lucas, Kurtz, and production supervisor Robert Watts. Under the new system, the project met the studio's deadline. [10][56] During production, the cast attempted to make Lucas laugh or smile, as he often appeared depressed. At one point, the project became so demanding that Lucas was diagnosed with hypertension and exhaustion and was warned to reduce his stress level. [10][56] Post-production was equally stressful due to increasing pressure from 20th Century Fox.The most significant material cut was a series of scenes from the first part of the film which served to introduce the character of Luke Skywalker. These early scenes, set in Anchorhead on the planet Tatooine, presented the audience with Luke's everyday life among his friends as it is affected by the space battle above the planet; they also introduced the character of Biggs Darklighter, Luke's closest friend who departs to join the Rebellion.

It also lacked most special effects; hand-drawn arrows took the place of blaster beams, and when the Millennium Falcon fought TIE fighters, the film cut to footage of World War II dogfights. [68] The reactions of the directors present, such as Brian De Palma, John Milius, and Steven Spielberg, disappointed Lucas. Spielberg, who claimed to have been the only person in the audience to have enjoyed the film, believed that the lack of enthusiasm was due to the absence of finished special effects. Lucas later said that the group was honest and seemed bemused by the film.

In contrast, Ladd and the other studio executives loved the film; Gareth Wigan told Lucas: "This is the greatest film I've ever seen" and cried during the screening. Lucas found the experience shocking and rewarding, having never gained any approval from studio executives before. The sequence was later re-instated in the 1997 Special Edition with a computer-generated version of Jabba. [70][71] Soundtrack Main article: Star Wars (soundtrack) Original vinyl release On the recommendation of his friend Steven Spielberg, Lucas hired composer John Williams. Williams had worked with Spielberg on the film Jaws, for which he won an Academy Award. Lucas felt that the film would portray visually foreign worlds, but that the musical score would give the audience an emotional familiarity; he wanted a grand musical sound for Star Wars, with leitmotifs to provide distinction. Therefore, he assembled his favorite orchestral pieces for the soundtrack, until Williams convinced him that an original score would be unique and more unified. However, a few of Williams' pieces were influenced by the tracks given to him by Lucas: the "Main Title Theme" was inspired by the theme from the 1942 film Kings Row, scored by Erich Wolfgang Korngold; and the track "Dune Sea of Tatooine" drew from the soundtrack of Bicycle Thieves, scored by Alessandro Cicognini. In March 1977, Williams conducted the London Symphony Orchestra to record the Star Wars soundtrack in 12 days. [10] The original soundtrack was released as a double LP in 1977 by 20th Century Records. 20th Century Fox released The Story of Star Wars that same year, which adapted the film and presented it as a narrated story with music, dialogue, and sound effects from the original film. The American Film Institute's list of best film scores ranks the Star Wars soundtrack at number one. [72] Cinematic and literary allusions This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (March 2015) See also: Star Wars sources and analogues War films such as the The Dam Busters and 633 Squadron, which used aircraft like the Avro Lancaster (top) and the Mosquito (bottom), respectively, were inspirations for the battle sequences According to Lucas, different concepts of the film were inspired by numerous sources, such as Beowulf and King Arthur for the origins of myth and religion.[73] Star Wars features several parallels to Flash Gordon, such as the conflict between Rebels and Imperial Forces, the wipes between scenes, the fusion of futuristic technology and traditional magic, and the famous opening crawl that begins each film. [74][75] The film has also been compared to The Wizard of Oz. [76][77] The influence of Kurosawa's 1958 film can be seen in the relationship between C-3PO and R2-D2, which evolved from the two bickering peasants in The Hidden Fortress, and a Japanese family crest seen in the earlier film is similar to the Imperial Crest.

Provide a small but reliable source of water. "[78] Frank Herbert reported that "David Lynch, [director of the 1984 film Dune] had trouble with the fact that Star Wars used up so much of Dune. The odds against coincidence produced a number larger than the number of stars in the universe.

[79] The Death Star assault scene was modeled after the World War II film The Dam Busters (1955), in which Royal Air Force Lancaster bombers fly along heavily defended reservoirs and aim bouncing bombs at dams, in order to cripple the heavy industry of Germany's Ruhr region. Some of the dialogue in The Dam Busters is repeated in the Star Wars climax; Gilbert Taylor also filmed the special effects sequences in The Dam Busters. In addition, the sequence was partially inspired by the climax of the film 633 Squadron (1964), directed by Walter Grauman, [80] in which RAF de Havilland Mosquitos attack a German heavy water plant by flying down a narrow fjord to drop special bombs at a precise point, while avoiding anti-aircraft guns and German fighters. Clips from both films were included in Lucas's temporary dogfight footage version of the sequence. [81] The opening shot of Star Wars, in which a detailed spaceship fills the screen overhead, is a reference to the scene introducing the interplanetary spacecraft Discovery One in Stanley Kubrick's seminal 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.The earlier big-budget science fiction film influenced the look of Star Wars in many other ways, including the use of EVA pods and hexagonal corridors. The Death Star has a docking bay reminiscent of the one on the orbiting space station in 2001. [82] Although golden and male, C-3PO was inspired by the robot Maria, the Maschinenmensch from Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis. [83] Release Premiere and initial release Lucasfilm hired Charles Lippincott as marketing director for Star Wars. As 20th Century Fox gave little support for marketing beyond licensing T-shirts and posters, Lippincott was forced to look elsewhere.

He secured deals with Marvel Comics for a comic book adaptation, and with Del Rey Books for a novelization. A fan of science fiction, he used his contacts to promote the film at the San Diego Comic-Con and elsewhere within science fiction fandom. [10][35] Worried that Star Wars would be beaten out by other summer films, such as Smokey and the Bandit, 20th Century Fox moved the release date to May 25, the Wednesday before Memorial Day. However, fewer than 40 theaters ordered the film to be shown. [10] On opening day I... Did a radio call-in show... This caller, was really enthusiastic and talking about the movie in really deep detail. I said,'You know a lot about the film. He said,'Yeah, yeah, I've seen it four times already. Producer Gary Kurtz, on when he realized Star Wars had become a cultural phenomenon[84] Star Wars debuted on Wednesday, May 25, 1977, in fewer than 32 theaters, and eight more on Thursday and Friday. Kurtz said in 2002, That would be laughable today. It immediately broke box office records, effectively becoming one of the first blockbuster films, and Fox accelerated plans to broaden its release. [35][85] Lucas himself was not able to predict how successful Star Wars would be. After visiting the set of the Steven Spielbergdirected Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Lucas was sure Close Encounters would outperform the yet-to-be-released Star Wars at the box office. Spielberg disagreed, and felt Lucas's Star Wars would be the bigger hit. Lucas proposed they trade 2.5% of the profit on each other's films; Spielberg took the trade, and still receives 2.5% of the profits from Star Wars. Having forgotten that the film would open that day, [87] he spent most of Wednesday in a sound studio in Los Angeles. When Lucas went out for lunch with Marcia, they encountered a long line of people along the sidewalks leading to Mann's Chinese Theatre, waiting to see Star Wars. [56] He was still skeptical of the film's success despite Ladd and the studio's enthusiastic reports. [87] The film was a huge success for the studio, and was credited for reinvigorating it.Within three weeks of its release, 20th Century Fox's stock price had doubled to a record high. [10] Although the film's cultural neutrality helped it to gain international success, Ladd became anxious during the premiere in Japan. After the screening, the audience was silent, leading him to fear that the film would be unsuccessful. [10] When Star Wars made an unprecedented second opening at Mann's Chinese Theatre on August 3, 1977, after William Friedkin's Sorcerer failed, thousands of people attended a ceremony in which C-3PO, R2-D2 and Darth Vader placed their footprints in the theater's forecourt.

[85][10] At that time Star Wars was playing in 1,096 theaters in the United States. [88] Approximately 60 theaters played the film continuously for over a year;[89] in 1978, Lucasfilm distributed "Birthday Cake" posters to those theaters for special events on May 25, the one-year anniversary of the film's release. [90] Later releases The 1997 theatrical release poster of the new Special Edition version of the film The film was originally released as Star Wars, without "Episode IV" or the subtitle A New Hope. [19] The subtitles were added starting with the film's theatrical re-release on April 10, 1981. [5][19] Star Wars was re-released theatrically in 1978; 1979; 1981; 1982; and, with additional scenes and enhanced special effects (further subtitled as the Special Edition), in 1997. [91] After ILM used computer-generated effects for Steven Spielberg's 1993 film Jurassic Park, Lucas concluded that digital technology had caught up to his original vision for Star Wars. [10] For the film's 20th anniversary in 1997, Star Wars was digitally remastered and re-released to movie theaters, along with The Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi, under the campaign title Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition. The Special Edition contained visual shots and scenes that were unachievable in the original release due to financial, technological, and time constraints; one such scene involved a meeting between Han Solo and Jabba the Hutt.[93] A particularly controversial change in which a bounty hunter named Greedo shoots first when confronting Han Solo has inspired T-shirts brandishing the phrase "Han Shot First". [94] Star Wars required extensive restoration before Lucas's Special Edition modifications could be attempted. It was discovered that in addition to the negative motion picture stocks commonly used on feature films, Lucas had also used internegative film, a reversal stock which deteriorated faster than negative stocks did. This meant that the entire printing negative had to be disassembled, and the CRI (color reversal internegative) portions cleaned separately from the negative portions.

Once the cleaning was complete, the film was scanned into the computer for restoration. In many cases, entire scenes had to be reconstructed from their individual elements. Fortunately, digital compositing technology allowed them to correct for problems such as alignment of mattes, "blue-spill", and so forth. [95] Though the original Star Wars was selected by the National Film Registry of the United States Library of Congress in 1989, [96] it is unclear whether a copy of the 1977 theatrical sequence or the 1997 Special Edition has been archived by the NFR, or indeed if any copy has been provided by Lucasfilm and accepted by the Registry.

[99] Home media Star Wars debuted on Betamax, [100] LaserDisc, [101] Video 2000, and VHS[102][103] between the 1980s and 1990s by CBS/Fox Video. [104] The film was released for the first time on DVD on September 21, 2004, in a box set with The Empire Strikes Back, Return of the Jedi, and a bonus disc of supplementary material. The films were digitally restored and remastered, and more changes were made by George Lucas. The DVD features a commentary track from Lucas, Ben Burtt, Dennis Muren, and Carrie Fisher. The bonus disc contains the documentary Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy, three featurettes, teasers, theatrical trailers, TV spots, still galleries, an exclusive preview of Episode III: Revenge of the Sith, a playable Xbox demo of the LucasArts game Star Wars: Battlefront, and a "Making Of" documentary on the Episode III video game. [105] The set was reissued in December 2005 as part of a three-disc limited edition boxed set without the bonus disc. [106] The trilogy was re-released on separate two-disc limited edition DVD sets from September 12 to December 31, 2006, and again in a limited edition tin box set on November 4, 2008;[107] the original versions of the films were added as bonus material. The release was met with criticism as the unaltered versions were from the 1993 non-anamorphic LaserDisc masters and were not re-transferred using modern video standards. The transfer led to problems with colors and digital image jarring.[108] All six Star Wars films were released by 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment on Blu-ray Disc on September 16, 2011 in three different editions, with A New Hope available in both a box set of the original trilogy[109][110] and with the other five films on Star Wars: The Complete Saga, which includes nine discs and over 40 hours of special features. [111] The original theatrical versions of the films were not included in the box set; however, the new 2011 revisions of the trilogy were leaked a month prior to release, inciting controversy the new changes made to these movies and causing an online uproar against Lucas. Disney will now possess the ownership rights to all six Star Wars films, under a previous deal with Lucasfilm, the full distribution rights to A New Hope will remain with Fox in perpetuity, while the physical distribution arrangements for the remaining films are set to expire in 2020 (Lucasfilm had retained the television and digital distribution rights to all Star Wars films produced after the original).

[115][116] On April 7, 2015, the Walt Disney Studios, 20th Century Fox, and Lucasfilm jointly announced the digital releases of the six released Star Wars films. Fox released A New Hope for digital download on April 10, 2015 (while Disney released the other five films). [116][117] Reception Box office Star Wars remains one of the most financially successful films of all time. [121] Reissues in 1978, 1979, 1981, and 1982 brought its cumulative gross in Canada and the U. [123] The film remained the highest-grossing film of all time until E. The Extra-Terrestrial broke that record in 1983.[124] Following the release of the Special Edition in 1997, [125] Star Wars briefly reclaimed the North American record before losing it again the following year to Titanic. [127] According to Guinness World Records, the film ranks as the third-highest-grossing film when adjusting for inflation;[128] at the North American box office, it ranks second behind Gone with the Wind on the inflation-adjusted list. [129] Critical response What makes the Star War experience unique, though, is that it happens on such an innocent and often funny level. It's usually violence that draws me so deeply into a movie violence ranging from the psychological torment of a Bergman character to the mindless crunch of a shark's jaws.

Maybe movies that scare us find the most direct route to our imaginations. But there's hardly any violence at all in Star Wars (and even then it's presented as essentially bloodless swashbuckling). Instead, there's entertainment so direct and simple that all of the complications of the modern movie seem to vaporize. Roger Ebert, in his review for the Chicago Sun-Times[130] The film was met with critical acclaim upon its release. In his 1977 review, Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times called the film "an out-of-body experience", compared its special effects to those of 2001: A Space Odyssey, and opined that the true strength of the film was its "pure narrative". [130] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "the movie that's going to entertain a lot of contemporary folk who have a soft spot for the virtually ritualized manners of comic-book adventure" and the most elaborate, most expensive, most beautiful movie serial ever made. Murphy of Variety described the film as "magnificent" and claimed George Lucas had succeeded in his attempt to create the "biggest possible adventure fantasy" based on the serials and older action epics from his childhood.Its consensus states in summary, A legendary expansive and ambitious start to the sci-fi saga, George Lucas opens our eyes to the possibilities of blockbuster film-making and things have never been the same. "[138] Metacritic reports an aggregate score of 92 out of 100 (based on 14 reviews), indicating "universal acclaim. [139] In his 1997 review of the film's 20th anniversary release, Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune gave the film four out of four stars, saying, A grandiose and violent epic with a simple and whimsical heart. "[140] A San Francisco Chronicle staff member described the film as "a thrilling experience.

"[141] Gene Siskel, writing for the Chicago Tribune in 1999, said, "What places it a sizable cut about the routine is its spectacular visual effects, the best since Stanley Kubrick's 2001. "[142] Andrew Collins of Empire magazine awarded the film five out of five and said, "Star Wars' timeless appeal lies in its easily identified, universal archetypesgoodies to root for, baddies to boo, a princess to be rescued and so onand if it is most obviously dated to the 70s by the special effects, so be it. "[143] In his 2009 review, Robert Hatch of The Nation called the film "an outrageously successful, what will be called a'classic,' compilation of nonsense, largely derived but thoroughly reconditioned.

I doubt that anyone will ever match it, though the imitations must already be on the drawing boards. "[144] In a more critical review, Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader stated, "None of these characters has any depth, and they're all treated like the fanciful props and settings. "[145] Peter Keough of the Boston Phoenix said, "Star Wars is a junkyard of cinematic gimcracks not unlike the Jawas' heap of purloined, discarded, barely functioning droids. [146] Accolades Alec Guinness, shown here in 1973, received multiple award nominations, including one from the Academy, for his performance as Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi The film garnered numerous accolades after its release.

Star Wars won six competitive Academy Awards at the 50th Academy Awards: Best Art Direction, Best Costume Design, Best Film Editing, Best Original Score, Best Sound and Best Visual Effects. A Special Achievement for Sound Effects Editing went to sound designer Ben Burtt[147] and a Scientific and Engineering Award went to John Dykstra for the development of the Dykstraflex Camera shared with Alvah J. Miller and Jerry Jeffress, who were both granted for the engineering of the Electronic Motion Control System. [148] Additional nominations included Alec Guinness for Best Actor in a Supporting Role and George Lucas for Best Original Screenplay, Best Director, and Best Picture, which were instead awarded to Woody Allen's Annie Hall. [147] At the 35th Golden Globe Awards, the film was nominated for Best Motion Picture Drama, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor (Alec Guinness), and it won the award for Best Score.

[149] It received six British Academy Film Awards nominations: Best Film, Best Editing, Best Costume Design, Best Production/Art Design, Best Sound, and Best Score; the film won in the latter two categories. [150] John Williams' soundtrack album won the Grammy Award for Best Album of Original Score for a Motion Picture or Television Program, [151] and the film attained the Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation. [152] The film also received twelve nominations at the Saturn Awards, winning nine: Best Science Fiction Film, Best Direction and Best Writing for George Lucas, Best Supporting Actor for Alec Guinness, Best Music for John Williams, Best Costume for John Mollo, Best Make-up for Rick Baker and Stuart Freeborn, Best Special Effects for John Dykstra and John Stears, and Outstanding Editing for Paul Hirsch, Marcia Lucas and Richard Chew.Approximately 400 mailboxes across the country were also designed to look like R2-D2. [178] Cinematic influence Film critic Roger Ebert wrote in his book The Great Movies, Like The Birth of a Nation and Citizen Kane, Star Wars was a technical watershed that influenced many of the movies that came after. [8] It began a new generation of special effects and high-energy motion pictures. The film was one of the first films to link genres together to invent a new, high-concept genre for filmmakers to build upon. [8][49] Finally, along with Steven Spielberg's Jaws, it shifted the film industry's focus away from personal filmmaking of the 1970s and towards fast-paced, big-budget blockbusters for younger audiences.

[8][10][179] Filmmakers who have said to have been influenced by Star Wars include James Cameron, Dean Devlin, Gareth Edwards, [180] Roland Emmerich, John Lasseter, [181] David Fincher, Peter Jackson, Joss Whedon, Christopher Nolan, Ridley Scott, John Singleton, and Kevin Smith. [49] Scott, Cameron, and Jackson were influenced by Lucas's concept of the "used future" (where vehicles and culture are obviously dated) and extended the concept for their films, such as Scott's science fiction films Alien (1979) and Blade Runner (1982), and Cameron's The Terminator (1984). Jackson used the concept for his production of The Lord of the Rings trilogy to add a sense of realism and believability. [49] Christopher Nolan cited Star Wars as an influence when making the 2010 blockbuster film, Inception. [182] Some critics have blamed Star Wars, as well as Jaws, for ruining Hollywood by shifting its focus from "sophisticated" films such as The Godfather, Taxi Driver, and Annie Hall to films about spectacle and juvenile fantasy.In an article intended for the cover of the issue, Time's Gerald Clarke wrote that Star Wars is a grand and glorious film that may well be the smash hit of 1977, and certainly is the best movie of the year so far. The result is a remarkable confection: a subliminal history of the movies, wrapped in a riveting tale of suspense and adventure, ornamented with some of the most ingenious special effects ever contrived for film. Each of the subsequent films of the Star Wars saga has appeared on the magazine's cover. Series AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (1998) #15[185]AFI's 100 Years...

100 Thrills (2001) #27[186]AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes & Villains (2003): Han Solo #14 Hero[187]Obi-Wan Kenobi #37 Hero[187]Princess Leia Nominated Hero[188]Luke Skywalker Nominated Hero[188]AFI's 100 Years...

100 Movie Quotes (2004): May the Force be with you. " #8[189]"Help me, Obi-Wan Kenobi. You're my only hope. Nominated[190]AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores (2005) #1[72]AFI's 100 Years... 100 Cheers (2006) #39[191]AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) (2007) #13[192]AFI's 10 Top 10 (2008) #2 Sci-Fi Film[193] American Film Institute[194] Star Wars was voted the second most popular film by Americans in a 2008 nationwide poll conducted by the market research firm, Harris Interactive. [195] Star Wars has also been featured in several high-profile audience polls: in 1997, it ranked as the 10th Greatest American Film on the Los Angeles Daily News Readers' Poll;[196] in 2002, the film and its sequel The Empire Strikes Back were voted as the greatest films ever made in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Films poll;[197] in 2011, it ranked as Best Sci-Fi Film on Best in Film: The Greatest Movies of Our Time, a primetime special aired by ABC that counted down the best films as chosen by fans, based on results of a poll conducted by ABC and People magazine; in 2014 the film placed 11th in a poll undertaken by The Hollywood Reporter, which balloted every studio, agency, publicity firm, and production house in the Hollywood region. [198] Reputable publications also have included Star Wars in their best films lists: in 2008, Empire magazine ranked Star Wars at No. 22 on its list of the "500 Greatest Movies of All Time";[199] in 2010, the film ranked among the "All-Time 100" list of the greatest films as chosen by Time magazine film critic Richard Schickel;[200] the film was also placed on a similar list created by The New York Times, "The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made";[201] in 2012, the film was included in Sight & Sound's prestigious decennial critics poll "Critics' Top 250 Films", ranking at 171st on the list, and in their directors poll at 224th. [202] Lucas's original screenplay was selected by the Writers Guild of America as the 68th greatest of all time. [203] In 1989, the Library of Congress selected Star Wars for preservation in the United States National Film Registry, as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant"[96] (though it remains unclear which edition, if any, the NFR has succeeded in acquiring from Lucasfilm);[97][98] its soundtrack was added to the United States National Recording Registry 15 years later (in 2004). [204] In addition to the film's multiple awards and nominations, Star Wars has also been recognized by the American Film Institute on several of its lists. The film ranks first on 100 Years of Film Scores, [72] second on Top 10 Sci-Fi Films, [193] 15th on 100 Years... 100 Movies[185] (ranked 13th on the updated 10th anniversary edition), [192] 27th on 100 Years... 100 Thrills, [186] and 39th on 100 Years... [191] In addition, the quote "May the Force be with you" is ranked eighth on 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes, [189] and Han Solo and Obi-Wan Kenobi are ranked as the 14th and 37th greatest heroes respectively on 100 Years... [187] Merchandising Main articles: Kenner Star Wars action figures, Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker, Star Wars (comics) and Star Wars (radio) Little Star Wars merchandise was available for several months after the film's debut, as only Kenner Products had accepted marketing director Charles Lippincott's licensing offers.The credited author was George Lucas, but the book was revealed to have been ghostwritten by Alan Dean Foster, who later wrote the first Expanded Universe novel, Splinter of the Mind's Eye (1978). The book was first published as Star Wars: From the Adventures of Luke Skywalker; later editions were titled simply Star Wars (1995) and, later, Star Wars: A New Hope (1997), to reflect the retitling of the film. Marketing director Charles Lippincott secured the deal with Del Rey Books to publish the novelization in November 1976. [10] Marvel Comics also adapted the film as the first six issues of its licensed Star Wars comic book, with the first issue dated May 1977. Roy Thomas was the writer and Howard Chaykin was the artist of the adaptation.

Like the novelization, it contained certain elements, such as the scene with Luke and Biggs, that appeared in the screenplay but not in the finished film. [68] The series was so successful that, according to Jim Shooter, it "single-handedly saved Marvel". [207] In 2013, Dark Horse Comics published a comic adaption of the original screenplay's plot. [208] Lucasfilm adapted the story for a children's book-and-record set. Released in 1979, the 24-page Star Wars read-along book was accompanied by a 33 rpm 7-inch phonograph record. Each page of the book contained a cropped frame from the movie with an abridged and condensed version of the story. The record was produced by Buena Vista Records, and its content was copyrighted by Black Falcon, Ltd. A subsidiary of Lucasfilm "formed to handle the merchandising for Star Wars". [209] The Story of Star Wars was a 1977 record album presenting an abridged version of the events depicted in Star Wars, using dialogue and sound effects from the original film. The recording was produced by George Lucas and Alan Livingston, and was narrated by Roscoe Lee Browne. The script was adapted by E. Jack Kaplan and Cheryl Gard. [citation needed] A radio drama adaptation of the film was written by Brian Daley, directed by John Madden, and produced for and broadcast on the American National Public Radio network in 1981. The adaptation received cooperation from George Lucas, who donated the rights to NPR. John Williams' music and Ben Burtt's sound design were retained for the show; Mark Hamill (Luke Skywalker) and Anthony Daniels (C-3PO) reprised their roles as well. The radio drama featured scenes not seen in the final cut of the film, such as Luke Skywalker's observation of the space battle above Tatooine through binoculars, a skyhopper race, and Darth Vader's interrogation of Princess Leia. In terms of Star Wars canon, the radio drama is given the highest designation (like the screenplay and novelization), G-canon. [210][211] This is a list of comic books set in the fictional Star Wars universe. Dark Horse Comics owned the license to publish Star Wars comics from LucasFilm exclusively from 1991 to 2014.LucasFilm's now-corporate sibling Marvel Comics, which published Star Wars comics from 1977 to 1986, are once again publishing Star Wars titles starting in 2015. The only comics considered canon are those released starting in 2015. For a complete list of Star Wars novels please refer to Star Wars books. This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

This list is split into two categories: CANON The new primary Star Wars canon includes all the movie episodes, the television shows Star Wars: The Clone Wars and Star Wars Rebels, books, comics, and video games published after April 2014, and comics published in 2015. These stories are coordinated by the Lucasfilm Story Team to be consistent with both each other and the upcoming films. LEGENDS These books are part of the original Star Wars Expanded Universe, and vary in levels of canonicity. The new films will not be based on these stories, but some parts may still be incorporated into the films.Obi-Wan & Anakin Star Wars: Obi-Wan & Anakin by Charles Soule (Between 32 and 22 BBY) Obi-Wan & Anakin (Issues #1-5) Darth Maul: Son of Dathomir Star Wars: Darth Maul: Son of Dathomir by Jeremy Barlow (20 BBY) The Enemy of My Enemy (Issue #1)A Tale of Two Apprentices (Issue #2)Proxy War (Issue #3)Showdown on Dathomir (Issue #4) Story Before the Force Awakens Star Wars: Story Before the Force Awakens by Hong Jac-ga Star Wars: Story Before the Force Awakens is a web comic by Korean artist and writer Hong Jac-ga. The strips are currently being translated to English and are available on. [1] An Old Friend (Issue #1) (12 BBY-6 BBY)Meeting the Droids (Issue #2) (6 BBY-0 BBY)Beginning of an Adventure (Issue #3) (0 BBY)Only Hope (Issue #4) (0 BBY)Escape (Issue #5) (0 BBY)Death Star (Issue #6) (0 BBY) Spans the Rise of the Empire Era and the Rebellion Era. Rebellion Era This era contains stories taking place within 6 years before and 4 years after Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Star Wars Rebels Comic Strips Published in the monthly Star Wars Rebels UK Magazine Ring Race (5 BBY)Learning Patience (5 BBY)The fake Jedi (5 BBY)Kallus' Hunt (5 BBY)Return of the Slavers (5 BBY)Eyes on the Prize (5 BBY)Sabotaged Supplies (5 BBY)Ezra's Vision (4 BBY)Senate Perspective (4 BBY) Kanan Star Wars: Kanan by Greg Weisman The Last Padawan, Part I: Fight (Issue #1) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 19 BBY)The Last Padawan, Part II: Flight (Issue #2) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 19 BBY)The Last Padawan, Part III: Pivot (Issue #3) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 19 BBY)The Last Padawan, Part IV: Catch (Issue #4) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 19 BBY)The Last Padawan, Part V: Release (Issue #5) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 19 BBY)The Last Padawan, Epilogue: Haunt (Issue #6) (5 BBY)First Blood (Issues #7-11) (5 BBY; flashbacks to 20 BBY) Princess Leia Star Wars: Princess Leia by Mark Waid (0 ABY) Princess Leia (Issues #1-5) Chewbacca Star Wars: Chewbacca by Gerry Duggan (0 ABY) Chewbacca (Issues #1-5) Star Wars Star Wars by Jason Aaron Skywalker Strikes (Issues #1-6) (0 ABY)From the Journals of Old Ben Kenobi: "The Last of His Breed" (Issue #7) (0 ABY; flashbacks to 11 BBY)Showdown on the Smuggler's Moon (Issues #8-12) (0 ABY)Vader Down, Part III (Issue #13) (0 ABY)Vader Down, Part V (Issue #14) (0 ABY)Annual 1 (Between 0 and 3 ABY) Darth Vader Star Wars: Darth Vader by Kieron Gillen Vader (Issues #1-6) (0 ABY)Shadows and Secrets (Issues #7-12) (0 ABY)Vader Down, Part II (Issue #13) (0 ABY)Vader Down, Part IV (Issue #14) (0 ABY)Vader Down, Part VI (Issue #15) (0 ABY)Annual 1 (Between 0 and 3 ABY) Vader Down Star Wars: Vader Down by Jason Aaron and Kieron Gillen (0 ABY) Vader Down is a six-issue crossover event series between Star Wars and Darth Vader.

Vader Down, Part I (Issue #1)Vader Down, Part II (Issue #2; Issue #13 of Darth Vader)Vader Down, Part III (Issue #3; Issue #13 of Star Wars)Vader Down, Part IV (Issue #4; Issue #14 of Darth Vader)Vader Down, Part V (Issue #5; Issue #14 of Star Wars)Vader Down, Part VI (Issue #6; Issue #15 of Darth Vader) Lando Star Wars: Lando by Charles Soule (Between 0 ABY and 3 ABY) Lando (Issues #1-5) Era of the New Republic This era contains stories taking place within 4 and 34 years after Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Shattered Empire Star Wars: Shattered Empire by Greg Rucka (4 ABY) Shattered Empire (Issues #1-4) C-3PO Star Wars Special: C-3PO 1 by James Robinson (After 4 ABY) One-shot comic Era of The First Order and The Resistance This era contains stories taking place approximately 34 years after Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope. Unknown Placement This section contains upcoming stories that do not yet have a known placement. Star Wars: Legends Before the Republic Era (37,000-25,000 BBY) Dawn of the Jedi 36,453 BBY Force Storm by John Ostrander (Dawn of the Jedi #1-5)The Prisoner of Bogan by John Ostrander (Dawn of the Jedi #6-10)The Force War by John Ostrander (Dawn of the Jedi #11-15) Old Galactic Republic Era a. The Sith Era (5,0001,000 BBY) Tales of the Jedi 5,000 BBY Tales of the Jedi: Golden Age of the Sith by Kevin J. Anderson 4,990 BBY Tales of the Jedi: The Fall of the Sith Empire by Kevin J. Anderson 4,000 BBY Tales of the Jedi: Knights of the Old Republic by Tom Veitch 3,998 BBY Tales of the Jedi: The Freedon Nadd Uprising by Tom Veitch 3,996 BBY Tales of the Jedi: Dark Lords of the Sith by Tom Veitch and Kevin J. AndersonTales of the Jedi: The Sith War by Kevin J. Anderson 3,993 BBY Shadows and Light by Joshua Ortega (published in Tales #23) 3,986 BBY Tales of the Jedi: Redemption by Kevin J. Anderson Knights of the Old Republic 3,964 BBY Crossroads by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #0, published in the Knights of the Old Republic / Rebellion Flip Book)Commencement by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #16)Flashpoint by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #78, 10) 3,963 BBY Flashpoint Interlude: Homecoming by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #9)Reunion by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #1112)Days of Fear by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #1315)Nights of Anger by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #1618)Daze of Hate by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #1921)Knights of Suffering by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #2224)Vector by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #2528)Exalted by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #29-30)Turnabout by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #31)Vindication by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #32-35)Prophet Motive by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #36-37)Faithful Execution by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #38)Dueling Ambitions by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #39-41)Masks by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #42)The Reaping by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #43-44)Destroyer by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #45-46)Demon by John Jackson Miller (Knights of the Old Republic #47-50) 3,962 BBY Knights of the Old Republic: War by John Jackson Miller 3,952 BBY Unseen, Unheard by Chris Avellone (published in Tales #24) Cold War 3,678 BBY The Old Republic: Blood of the Empire by Alexander Freed 3,653 BBY The Old Republic: Threat of Peace by Rob Chestney 3,643 BBY The Old Republic: The Lost Suns by Alexander Freed 2,975 BBY Lost Tribe of the Sith: Spiral by John Jackson Miller Knight Errant 1,032 BBY Aflame by John Jackson Miller (Knight Errant #1-5)Deluge by John Jackson Miller (Knight Errant #6-10)Escape by John Jackson Miller (Knight Errant #11-15) The Battle of Ruusan 1,000 BBY Jedi vs. Sith by Darko Macan Rise of the Empire Era (1,0000 BBY) Prelude to War 1000 BBY The Apprentice by Mike Denning (published in Tales #17) 996 BBY All For You by Adam Gallardo (published in Tales #17) 700 BBY Heart of Darkness by Paul Lee (published in Tales #16) 245 BBY Yaddle's Tale: The One Below by Dean Motter (published in Tales #5) 67 BBY Vow of Justice by Jan Strnad (published in Star Wars: Republic #46) 58 BBY Stones by Haden Blackman (published in Tales #13) 53 BBY Jedi - The Dark Side by Scott Allie 45 BBY Survivors by Jim Krueger (published in Tales #13)George R. Binks by Dave McCaig (published in Tales #20) 44 BBY Mythology by Chris Eliopoulos (published in Tales #14) 43 BBY The Secret of Tet Ami by Fabian Nicieza (published in Tales #13) 38 BBY Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan: The Aurorient Express by Mike Kennedy 37 BBY Once Bitten by C. Cebulski (published in Tales #12) 36 BBY Children of the Force by Jason Hall (published in Tales #13)Qui-Gon and Obi-Wan: Last Stand on Ord Mantell by Ryder WindhamAurra's Song by Dean Motter (published in Dark Horse Presents Annual 2000) 34 BBY Nameless by Christian Read (published in Tales #10) 33 BBY Marked by Rob Williams (published in Tales #24)Urchins by Stan Sakai (published in Tales #14)Jedi Council: Acts of War by Randy StradleyA Summer's Dream by Terry Moore (published in Tales #5)Life, Death, and the Living Force by Jim Woodring (published in Tales #1)Incident at Horn Station by Dan Jolley (published in Tales #2) 32.5 BBY Prelude to Rebellion by Jan Strnad (Star Wars: Republic #16)Single Cell by Haden Blackman (published in Tales #7)Darth Maul by Ron MarzThe Death of Captain Tarpals by Ryder Windham (published in Tales #3) The Phantom Menace 32 BBY Episode I: The Phantom MenaceEpisode I: The Phantom Menace (manga) by Kia AsamiyaEpisode I: The Phantom Menace AdventuresPodracing Tales by Ryder Windham (online comic)Outlander by Tim Truman (Star Wars: Republic #712)Deal with a Demon by John Ostrander (published in Tales #3)Nomad by Rob Williams (published in Tales #21-24)Emissaries to Malastare by Tim Truman (Star Wars: Republic #1318)Jango Fett: Open Seasons by Haden Blackman The Calm Before the Storm 31 BBY Twilight by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #1922)Infinity's End by Pat Mills (Star Wars: Republic #2326)Starcrash by Doug Petrie (Star Wars: Republic #27) 30 BBY The Stark Hyperspace War by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #3639)Bad Business by John Ostrander (published in Tales #8)The Hunt for Aurra Sing by Tim Truman (Star Wars: Republic #2831)Heart of Fire by John Ostrander (published in Dark Horse Extra #35-37)Darkness by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #3235)The Devaronian Version by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #4041) 28 BBY Rite of Passage by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #4245)Jedi Quest by Ryder Windham 27 BBY Jango Fett by Ron MarzZam Wesell by Ron MarzAurra Sing by Timothy Truman (published in The Bounty Hunters)The Sith in Shadow by Bob Harris (published in Tales #13) 25 BBY Poison Moon by Michael Carriglitto (published in Dark Horse Extra #44-47) 24 BBY A Jedi's Weapon by Henry Gilroy (published in Tales #12)Starfighter: Crossbones by Haden BlackmanPuzzle Peace by Scott Beatty (published in Tales #13)Honor and Duty by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #4648) 23 BBY Way of the Warrior by Peter Alilunas (published in Tales #18)Full of Surprises by Jason Hall (published in Hasbro/Toys"R"Us Exclusive) Most Precious Weapon by Jason Hall (published in Hasbro/Toys"R"Us Exclusive)Practice Makes Perfect by Jason Hall (published in Hasbro/Toys"R"Us Exclusive)Machines of War by Jason Hall (published in Hasbro/Toys"R"Us Exclusive) Attack of the Clones/The Clone Wars 22 BBY Episode II: Attack of the Clones by Henry GilroyClone Wars Volume 1: The Defense of Kamino by John Ostrander, Jan Duursema, Haden Blackman and Scott Allie Published by Titan Books Ltd. Sacrifice by John Ostrander (Republic #49)The Battle of Kamino by John Ostrander, Haden Blackman and Scott Allie (Republic #50)Jedi: Mace Windu by John OstranderClone Wars Volume 2: Victories and Sacrifices by Haden Blackman, John Ostrander, Tomas Giorello and Jan Duursema Published by Titan Books Ltd. The New Face of War by Haden Blackman (Republic #5152)Blast Radius by Haden Blackman (Republic #53)Jedi: Shaak Ti by John OstranderNobody's Perfect by Peter Bagge (published in Tales #20)The Lesson by Adam Gallardo (published in Tales #14)Tides of Terror by Milton Freewater Jr. (published in Tales #14)Clone Wars Adventures Volume 1 Blind Force by Haden BlackmanHeavy Metal Jedi by Haden BlackmanFierce Currents by Haden BlackmanClone Wars Adventures Volume 2 Skywalkers by Haden BlackmanHide in Plain Sight by Welles HartleyRun Mace Run by Matthew and Shawn FillbachClone Wars Adventures Volume 3 Rogues Gallery by Haden BlackmanThe Package by Matthew and Shawn FillbachStranger in Town by Matthew and Shawn FillbachOne Battle by Bytim MucciClone Wars Adventures Volume 4 Another Fine Mess by Matthew and Shawn FillbachThe Brink by Justin LambrosOrders by Ryan KaufmanDescent by Haden BlackmanClone Wars Adventures Volume 7Clone Wars Adventures Volume 8Clone Wars Adventures Volume 9 Appetite for Adventure by Matthew and Shawn FillbachSalvaged by Matthew and Shawn FillbachLife Below by Matthew and Shawn FillbachNo Way Out by Matthew and Shawn FillbachClone Wars Adventures Volume 10 Graduation Day by Chris AvelloneThunder Road by Matthew and Shawn FillbachChain of Command by Jason HallWaiting by Matthew and Shawn FillbachDark Journey by Jason Hall (published in Tales #17) 21.5 BBY Clone Wars Volume 4: Light and Dark by John Ostrander, Jan Duursema and Dan Parsons Published by Titan Books Ltd. Double Blind by John Ostrander (Republic #54)Jedi: Aayla Secura by John OstranderJedi: Dooku by John OstranderStriking from the Shadows by John Ostrander (Republic #63) 21 BBY Honor Bound by Ian Edginton (published in Tales #22)Rather Darkness Visible by Jeremy Barlow (published in Tales #19)Clone Wars Volume 3: Last Stand on Jabiim by Haden Blackman, Brian Ching, Victor Llamas Published by Titan Books Ltd. The Battle of Jabiim by Haden Blackman (Republic #5558)Enemy Lines by Haden Blackman (Republic #59)Clone Wars Volume 5: The Best Blades by John Ostrander, Haden Blackman, Jeremy Barlow, and Tomas Giorello Published by Titan Books Ltd. Hate and Fear by Haden Blackman (Republic #60)Dead Ends by John Ostrander (Republic #61)No Man's Land by John Ostrander (Republic #62)Bloodlines by John Ostrander (Republic #64)Jedi: Yoda by Jeremy BarlowClone Wars Volume 6: On The Fields of Battle by John Ostrander, Jan Duursema and Dan Parsons Published by Titan Books Ltd. Show of Force by John Ostrander (Republic #65-66)Forever Young by John Ostrander (Republic #67)Armor by John Ostrander (Republic #68)The Dreadnaughts of Rendili by John Ostrander (Republic #6971)Slaves of the Republic by Henry Gilroy (The Clone Wars #16)In the Service of the Republic by Henry Gilroy & Steven Melching (The Clone Wars #79)Hero of the Confederacy by Henry Gilroy & Steven Melching (The Clone Wars #1012)The Clone Wars - Online-Comic #122The Clone Wars: Gauntlet of Death by Henry Gilroy (2009 Free Comic Book Day)The Clone Wars (TV show tie-in novellas) #1-10Star Wars - Blood Ties : A Tale of Jango & Boba Fett by Tom Taylor & Chris Scalf 20 BBY General Grievous by Chuck DixonRoutine Valor by Randy Stradley (2006 Free Comic Book Day)Star Wars: Darth MaulDeath Sentence by Tom Taylor 19.5 BBY Clone Wars Volume 7: When They Were Brothers by Haden Blackman and Brian Ching Published by Titan Books Ltd. Obsession by Haden BlackmanUnnamed (2005 Free Comic Book Day)Clone Wars Volume 8: Last Siege, The Final Truth by John Ostrander, Jan Duursema and Dan Parsons Published by Titan Books Ltd. Trackdown by John Ostrander (Republic #7273)Siege of Saleucami by John Ostrander (Republic #7477)Brothers in Arms by Miles Lane (2005 Free Comic Book Day comic)Clone Wars Adventures Volume 5 What Goes Up by Matthew and Shawn FillbachBailed Out by Justin LambrosHeroes on Both Side by Chris AvelloneOrder of Outcasts by Matt Jacobs (published in Clone Wars Adventures Volume 5)Clone Wars Adventures Volume 6 Means and Ends by Haden BlackmanThe Drop by Mike KennedyTo The Vanishing Point by Matthew and Shawn FillbachIt Takes a Thief by Matthew and Shawn FillbachEvasive Action: Reversal of Fortune by Paul Ens Revenge of the Sith 19 BBY Episode III: Revenge of the Sith by Miles LaneLoyalties by John Ostrander (Star Wars: Republic #78)Clone Wars Volume 9: Endgame by John Ostrander, Jan Duursema and Brad Anderson Published by Titan Books Ltd. Into the Unknown (Star Wars: Republic #7980)The Hidden Enemy by John Ostrander (Republic #8183)Purge by John OstranderPurge - Seconds to Die by John OstranderPurge - The Hidden Blade by W.Haden BlackmanPurge - The Tyrant's Fist by Alexander FreedEvasive Action: Recruitment by Paul EnsEvasive Action: Prey by Paul EnsThe Path to Nowhere by Mick Harrison (Dark Times #15)Parallels by Mick Harrison (Dark Times #610)Vector by Mick Harrison (Dark Times #1112)Blue Harvest by Mick Harrison (Dark Times #0,1317)Darth Vader and the Lost Command by Hayden BlackmanOut of the Wilderness by Mick Harrison (Dark Times #18-22)Darth Vader and the Ghost Prison by Hayden BlackmanDarth Maul: Death Sentence by Tom TaylorDark Times: Fire Carrier by Mick HarrisonDark Times: A Spark Remains by Mick Harrison 18 BBY The Duty by Christian Read (published in Tales #12) 18-5 BBY The Value of Proper Intelligence to Any Successful Military Campaign is Not to be Underestimated by Ken Lizzi (published in Tales #19)Darth Vader and the Ninth Assassin by Tim Siedell 17 BBY Darth Vader and the Cry of Shadows by Tim Siedell 15 BBY Star Wars: Droids #1-5 by David Manak (Marvel Comics) 12 BBY Ghost by Jan Duursema (published in Tales #11)Fortune, Fate, and the Natural History of the Sarlacc by Mark Schultz (published in Tales #6) 11 BBY Nerf Herder by Phil Amara (published in Tales #7) 10 BBY Star Wars Blood Ties: Boba Fett is Dead by Tom Taylor 8 BBY Luke Skywalker: Detective by Rick Geary (published in Tales #20) 7 BBY Number Two in the Galaxy by Henry Gilroy (published in Tales #18)Payback by Andy Diggle (published in Tales #18)Being Boba Fett by Jason Hall (published in Tales #18) 6 BBY The Princess Leia Diaries (pages 17) by Jason Hall (published in Tales #11)Outbid but Never Outgunned by Beau Smith (published in Tales #7) The Dark Times 5 BBY Luke Skywalker: Walkabout by Phill Norwood (published in Dark Horse Presents Annual 1999)Routine by Tony Isabella (published in Tales #2)Young Lando Calrissian by Gilbert Hernandez (published in Tales #20)The Princess Leia Diaries (pages 89) by Jason Hall (published in Tales #11)Jabba the Hutt: The Art of the Deal by Jim Woodring 4 BBY Falling Star by Jim Beard (published in Tales #15)Star Wars: Ewoks #1-9 by David Manak 3 BBY The Flight of the Falcon by Steve Parkhouse (published in Devilworlds #1)In the Beginning by Garth Ennis (published in Tales #11)Star Wars: Droids: The Kalarba Adventures by Dan Thorsland (Dark Horse series V1 #1-6)Star Wars: Droids Special #1 by Dan ThorslandStar Wars: Droids: Rebellion by Ryder Windham (Dark Horse series V2 #1-4)Star Wars: Droids: The Season of Revolt by Jan Strnad (Dark Horse series V2 #5-8)Star Wars: Droids: The Protocol Offensive by Ryder WindhamStar Wars: Ewoks #10-14 by David ManakIron Eclipse by John Ostrander (Agent of the Empire #1-5)Hard Targets by John Ostrander (Agent of the Empire #6-10) 2 BBY Han Solo at Stars' End by Archie Goodwin (reprints strips by Alfredo Alcala)Crumb for Hire by Ryder Windham (published in A Decade of Dark Horse #2)Boba Fett: Salvage by John Wagner (published in Boba Fett ½)Boba Fett: Enemy of the Empire by John WagnerFirst Impressions by Nathan Walker (published in Tales #15)The Force Unleashed by Haden Blackman 1 BBY The Force Unleashed II by Haden BlackmanBlood Ties: Boba Fett is Dead by Tom TaylorDarklighter by Paul Chadwick (Empire #89, 12, 15)The Princess Leia Diaries (pages 1012) by Jason Hall (published in Tales #11)Darth Vader: Extinction by Ron Marz (published in Tales #1-2)The Hovel on Terk Street by Tom Fassbender and Jom Pascoe (published in Tales #6)Rookies Rendezvous by Pablo HidalgoRookies Rendezvous: No Turning Back by Pablo HidalgoWay of the Wookiee by Archie Goodwin (published in Marvel Illustrated Books Star Wars 1)Princess Warrior by Randy Stradley (Empire #56)Betrayal by Scott Allie (Empire #14)Dark Forces: Soldier for the Empire by William C. DietzThe Short, Happy Life of Roons Sewell by Paul Chadwick (Empire #1011)Star Wars Underworld - The Yavin Vassilika by Mike Kennedy & Carlos MegliaStar Wars Adventures: Han Solo and the Hollow Moon of Khorya The Rebellion Era (05 ABY) A New Hope 0 ABY Episode IV: A New Hope by Bruce JonesEpisode IV: A New Hope (manga) by Hisao TamakiX-wing Rogue Squadron #1/2 by Michael A.

Stackpole (Special Wizard Magazine comic)Droids #6-8 by David Manak (Marvel Comics)Trooper by Garth Ennis (published in Tales #10)What Sin Loyalty? By Jeremy Barlow (Empire #13)Day After the Death Star by Archie GoodwinSacrifice by John Wagner (Empire #7)The Savage Heart by Paul Alden (Empire #14)To the Last Man by Welles Hartley (Empire #16-18)Star Wars by Brian Wood, Carlos DAnda Volume 1: In The Shadow Of Yavin (#1-6)Volume 2: From The Ruins Of Alderaan (#7-12)Volume 3: Rebel Girl (#15-18)Volume 4: A Shattered Hope (#13-14, #19-20)Classic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 1: Doomworld by Archie Goodwin (collects Marvel Star Wars #1-20) Six Against the GalaxyDeath StarIn Battle with Darth VaderLo, The Moons of YavinIs This the Final Chapter? New Planets, New PerilsEight for Aduba-3Showdown on a Wasteland WorldBehemoth from the World BelowStar SearchDoomworldDay of the Dragon LordsThe Sound of ArmageddonStar DuelThe HunterCrucibleThe Empire StrikesThe Ultimate GambleDeathgameClassic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 2: Dark Encounters by Archie Goodwin (collects Marvel Star Wars #21-38 & Annual #1) Shadow of a Dark LordTo the Last GladiatorFlight Into FurySilent DriftingSiege at YavinDoom MissionReturn of the HunterWhat Ever Happened to Jabba the Hut? Dark EncounterA Princess AloneReturn to TatooineThe Jawa ExpressSaber ClashThunder in the StarsDark Lord's GambitRed Queen RisingIn Mortal CombatRiders in the VoidThe Long HuntClassic Star Wars Volume 1: Deadly Pursuit by Archie Goodwin The Bounty Hunter of Ord MantellDarth Vader StrikesThe Serpent MastersDeadly ReunionTraitor's GambitClassic Star Wars Volume 2: The Rebel Storm by Archie Goodwin The Night BeastThe Return of Ben KenobiThe Power GemThe Ice WorldRevenge of the JediDoom Mission! Classic Star Wars Volume 3: Escape to Hoth by Archie Goodwin Race For SurvivalThe Paradise DetourA New BeginningShowdown! Classic Star Wars, Volume 4: The Early Adventures by Russ Manning Gambler's WorldTatooine Sojourn (written by Steve Gerber)Princess Leia, Imperial Servant written by Archie Goodwin as R. HelmThe Second Kessel Run written by Archie Goodwin as R. Volume 3: Resurrection of Evil (collects Marvel's Star Wars #39-53) Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back The Empire Strikes Back: Beginning by Archie GoodwinThe Empire Strikes Back: Battleground: Hoth by Archie GoodwinThe Empire Strikes Back: Imperial Pursuit by Archie GoodwinThe Empire Strikes Back: To Be a Jedi by Archie GoodwinThe Empire Strikes Back: Betrayal at Bespin by Archie GoodwinThe Empire Strikes Back: Duel a Dark Lord by Archie GoodwinDeath Probe by Archie GoodwinThe Dreams of Cody Sunn-Childe by J. DeMatteisDroid World by Archie GoodwinThe Third Law by Larry HamaThe Last Jedi by Mike W. BarrThe Crimson Forever by Archie GoodwinResurrection of Evil by David MichelinieTo Take The Tarkin by David MichelinieThe Last Gift From Alderaan by Chris ClaremontClassic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 4: Screams in the Void (collects Marvel's Star Wars #54-67 & Annual #2)Classic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 5: Fool's Bounty (collects Marvel's Star Wars #68-81 & Annual #3)Moment of Doubt by Lovern Kindzierski (published in Tales #4)Slippery Slope by Scott Lobdell (published in Tales #15)Thank the Maker by Ryder Windham (published in Tales #6)Hunger Pains by Jim Campbell (published in Tales #20)Blind Fury by Alan Moore (published in Devilworlds #1)Tales from Mos Eisley by Bruce JonesShadow Stalker by Ryder WindhamShadows of the Empire by John WagnerBattle of the Bounty Hunters pop-up comic by Ryder WindhamScoundrel's Wages by Mark Schultz (published in The Bounty Hunters)Star Wars Adventures: Luke Skywalker and the Treasure of the Dragonsnakes by Tom TaylorStar Wars Adventures: The Will of Darth Vader by Tom Taylor Return of the Jedi 4 ABY Episode VI: Return of the Jedi by Archie GoodwinEpisode VI: Return of the Jedi (manga) by Shin-ichi HiromotoMara Jade: By the Emperor's Hand by Timothy Zahn and Michael A. StackpoleThe Jabba Tape by John WagnerSand Blasted by Killian Pluckett (published in Tales #4)A Day in the Life by Brett Matthews (published in Tales #12)Free Memory by Brett Matthews (published in Tales #10)Lucky by Rob Williams (published in Tales #23)Do or Do Not by Jay Laird (published in Tales #15)X-Wing: Rogue Leader by Haden BlackmanClassic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 6: Wookiee World (collects Marvel's Star Wars #82-95)Classic Star Wars: A Long Time Ago... Volume 7: Far, Far Away (collects Marvel's Star Wars #96-107)Classic Star Wars: The Vandelhelm Mission by Archie Goodwin and Al Williamson (reprints Marvel's Star Wars #98) New Galactic Republic Era (525 ABY) 5 ABY Mara Jade: A Night on the Town by Timothy Zahn (published in Tales #1)Marooned by Lucas Marangon (published in Tales #22)Three Against the Galaxy by Rich Hedden (published in Tales #3)Boba Fett: Agent of Doom by John OstranderX-wing Rogue Squadron Special (Kellogg's Apple Jacks Promotion) by Ryder Windham (also published in the Battleground Tatooine TPB)The Rebel Opposition by Michael A.Stackpole (X-wing Rogue Squadron #14)The Phantom Affair by Michael A. Stackpole (X-wing Rogue Squadron #58)Battleground: Tatooine by Michael A. Stackpole (X-wing Rogue Squadron #912)The Warrior Princess by Michael A.

Thomas became an early and active member of Silver Age comic book fandom when it organized in the early 1960s primarily around Jerry Bails, whose enthusiasm for the rebirth of superhero comics during that period led Bails to found the fanzine Alter Ego, an early focal point of fandom. Thomas, then a high school English teacher, took over as editor in 1964 when Bails moved on to other pursuits.

Letters from him appeared regularly in the letters pages of both DC and Marvel Comics, including The Flash #116 Nov. 1960, Fantastic Four #5 (July 1962), Fantastic Four #15 (June 1963), and Fantastic Four #22 Jan. Career Marvel Comics In 1965, Thomas moved to New York City to take a job at DC Comics as assistant to Mort Weisinger, then the editor of the Superman titles. Thomas said he had just accepted a fellowship to study foreign relations at George Washington University when he received a letter from Weisinger, "with whom I had exchanged one or two letters, tops", asking Thomas to become his assistant editor on a several-week trial basis."[5] Thomas had already written a Jimmy Olsen script "a few months before, while still living and teaching in the St. Louis area, he said in 2005. "I worked at DC for eight days in late June and very early July of 1965"[6] before accepting a job at Marvel Comics. The Marvel "Bullpen Bulletins" in Fantastic Four #61 (April 1967) describes Thomas admitting that he gave up a scholarship to George Washington University just to write for Marvel!

" This came after his chafing under the notoriously difficult Weisinger, to a point, Thomas said in 1981, that he would go "home to my dingy little room at, coincidentally, the George Washington Hotel in Manhattan, during that second week, and actually feeling tears well into my eyes, at the ripe old age of 24. "[5] Familiar with editor and chief writer Stan Lee's Marvel work, and feeling them "the most vital comics around, [5] Thomas just sat down one night at the hotel and I wrote him a letter! I figured he just might remember me from Alter Ego. [5] Lee did, and phoned Thomas to offer him a Marvel writing test. I was hired after taking [the]' writer's test', and my first official job title at Marvel was'staff writer'.

I wasn't hired as an editor or assistant editor. I was supposed to come in 40 hours a week and write scripts on staff. I sat at this corrugated metal desk with a typewriter in a small office with production manager Sol Brodsky and corresponding secretary Flo Steinberg. Almost at once, even though Stan proofed all the finished stories, he and Sol started having me check the corrections before they went out, and that would break up my concentration still further. [and] they kept asking me to do this or that, or questions like in which issue something happened, or Stan would come in to check something, because I knew a lot about Marvel continuity up to that time. It quickly became apparent to them, too, that the staff writer thing wasn't working, and Stan segued me over to being an editorial assistant, which immediately worked out better for all concerned. [7] The writer's test, Thomas said in 1998, was four Jack Kirby pages from Fantastic Four Annual #2... [Stan Lee] had Sol [Brodsky] or someone take out the dialogue. Other people like Denny O'Neil and Gary Friedrich took it. But soon afterwards we stopped using it. [8] The day after taking the test, Thomas was at DC, proofreading a Supergirl story, when Steinberg called asking Thomas to meet with Lee during lunch, where Thomas agreed to work for Marvel. "[9] His employment was announced in the "Bullpen Bulletins section of Fantastic Four #47 Feb. 1966 under the heading How About That! Department" "Roy's a fan who's made it! To that point, editor-in-chief Lee had been the main writer of Marvel publications, with his brother, Larry Lieber, often picking up the slack scripting Lee-plotted stories. Thomas soon became the first new Marvel writer to sustain a presence, at a time when comics veterans such as Robert Bernstein, Ernie Hart, Leon Lazarus, and Don Rico, and fellow newcomers Steve Skeates (hired a couple of weeks earlier) and O'Neil (brought in at Thomas' recommendation a few months later) did not. His Marvel debut was the romance-comics story Whom Can I Turn To? In the Millie the Model spin-off Modeling with Millie #44 Dec.[23][24][25] Thomas was the first person other than Stan Lee to receive a writer's credit for The Amazing Spider-Man, [26] and he and artist Ross Andru launched the Spider-Man spin-off title Marvel Team-Up in March 1972. [27] Thomas co-created many other characters with Marvel artists. Among them are Ultron (including the fictional metal adamantium), [28][29] Carol Danvers, [30] Morbius the Living Vampire, [26] Doc Samson, Valkyrie, Werewolf by Night, [31] and Killraven.

Reviving the Golden Age group in Justice League of America #193 and continuing in All-Star Squadron, [61] he wrote retro adventures, like those of The Invaders, set in World War II. In addition to the JSA's high-profile heroes, Thomas revived such characters as Liberty Belle, Johnny Quick, the Shining Knight, Robotman, Firebrand, the Tarantula, and Neptune Perkins.

The characters debuted in All-Star Squadron #25 Sept. 1983[63] and were launched in their own series in March 1984. [64] Thomas wrote several limited series for DC including America vs. The Justice Society, [65] Jonni Thunder a.

The New Beginning, and Crimson Avenger. From 1986 to 1988, Thomas contributed to the Secret Origins series[66] and wrote most of the stories involving the Golden Age characters including Superman and Batman. [67] In 1986, DC decided to write off the JSA from active continuity. A one-shot issue titled The Last Days of the Justice Society involved most of the JSA battling the forces of evil while merged with the Norse gods in an ever-repeating Ragnarok-like Limbo was written by Thomas, with art by David Ross. [68] Young All-Stars replaced All-Star Squadron following the changes to DC's continuity brought about by the Crisis on Infinite Earths limited series. Thomas's last major project for DC was an adaptation of Richard Wagner's Ring cycle drawn by Gil Kane and published in 19891990. Since then, Thomas has written a trio of Elseworlds one-shots combining DC characters with classic cinema and literature: Superman's Metropolis, Superman: War of the Worlds, and JLA: The Island of Dr.[12] Later career Thomas and Gerry Conway collaborated on the screenplays for two movies: the animated feature Fire and Ice (1983) and Conan the Destroyer (1984). I've even long regretted the fact that your elevation to the position of editor-in-chief, in which you've obviously done a fine job, came at a time after I'd moved to the West Coast.

Perhaps if we'd had more personal communication from 1977 to 1980, we could have come to some sort of agreement at that time or at least parted under more amicable circumstances. I leave it to you to decide if we should ever make any attempt to rectify that situation; certainly I've never been a grudge-carrier in other cases.... [70] By 1986, Thomas had begun writing for Marvel's New Universe line, beginning with Spitfire and the Troubleshooters #5 Feb. He then embarked on a multi-issue run of Nightmask, co-scripted by his wife Dann Thomas.[12][72] In 2012 he teamed with artists Mike Hawthorne and Dan Panosian on Dark Horse's Conan:The Road of Kings, which lasted 12 issues. In 2014, he wrote 75 Years of Marvel: From the Golden Age to the Silver Screen for Taschen, a 700 page hardcover history of Marvel Comics.

[4] I'd heard on the grapevine that Gil's assistant had dropped dead of a heart attack at 23. I gave Gil a call, and he said,'Yeah, I can use you.

So I went to work for him. He was doing [the early graphic novel] Blackmark, and I did a really bad job pasting up the dialog and putting in [Zip-a-Tone].... It was a great apprenticeship. I learned a lot from watching Gil work. [5] In 1970, he began publishing his art in comics and science-fiction fanzines, sometimes under the pseudonym Eric Pave. [3] Leaving Kane, he began working as an assistant to comics artist Wally Wood[6] in the studio he shared with Syd Shores and Jack Abel in Valley Stream, Long Island. He worked there for a "couple of months", [5] and in 1971 published his first professional comics work, for the adult-theme Western feature Shattuck in the military newspaper the Overseas Weekly, [3] one of Wood's clients. He also "ghosted some stuff" for Gray Morrow: I penciled a Man-Thing story he did for Marvel Comics' Fear #10 cover-dated Oct. 1972, and I penciled a thing for [the magazine] National Lampoon called Michael Rockefeller and the Jungles of New Guinea. [5][7] He then apprenticed under Neal Adams, working with the artist at Adams' home in The Bronx. [5] This led to his first work at DC Comics, one of the two largest comics companies: Neal showed me to [editors] Murray Boltinoff and Julius Schwartz.In 1976, Chaykin landed the job of drawing the Marvel Comics adaptation of the first Star Wars film, written by Roy Thomas. [9][14][15] This proved successful for Marvel, but Chaykin left after ten issues to work in more adult and experimental comics, as well the more lucrative field of paperback book covers. In fall 1978, [16] Chaykin, Walt Simonson, Val Mayerik, and Jim Starlin formed Upstart Associates, a shared studio space on West 29th Street in New York City. The membership of the studio changed over time.

[17] Chaykin penciled DC Comics' first miniseries, The World of Krypton (JulySeptember 1979). [18][19] In the next few years he produced material for Heavy Metal, drew a graphic novel adaptation of Alfred Besters The Stars My Destination, and produced illustrations for works by Roger Zelazny. Chaykin collaborated on two original graphic novels Swords of Heaven, Flowers of Hell with writer Michael Moorcock, and Empire with Samuel R. Delany and found time to move into film design with work on the movie version of Heavy Metal. 1980s American Flagg #2 Nov.

Chaykin had a six-issue run on Marvel's Micronauts series and drew issues #13 Jan. 1980 to #18 (June 1980). [20] He went back to Cody Starbuck with a story in Heavy Metal between May and September 1981, in the same painted art style he'd used for the Moorcock graphic novel. In 1983, Chaykin launched American Flagg!In 1987, a four-issue run was released, then the title was cancelled and relaunched as Howard Chaykins American Flagg! This new rendition failed to recapture the glory days of the titles early years and only lasted 12 issues before cancellation. The first new project was a controversial revamp of The Shadow in a four-issue miniseries for DC Comics in 1986.

Rather than setting the series in its traditional 1930s milieu, Chaykin updated it to a contemporary setting and included his own style of extreme violence. In a 2012 interview, Chaykin stated The reason I pulled him out of the period was because I thought it would be commercial suicide to do a period character at that point. Special one-shot was designed to introduce Chaykin's next major work, a graphic novel series called Time².Chaykin has described Time² as the single work about which he is most proud. [4] "To tell you the truth, my first interest would be to do another Time² because that was a very personal product for me, " he said in a 2008 interview. It's a fantasia of my family's story. [24] Before returning to American Flagg! Chaykin revamped another DC Comics character: Blackhawk was a three-issue mini-series that gave Chaykin another chance to indulge in the 1930s milieu, proving itself another successful revamping of a defunct DC character.

When DC proposed a system of labelling comics for violent or sexual content, Chaykin (with Alan Moore and Frank Miller) boycotted DC and refused to work for the company. In Chaykins case, the boycott would only last until the early 1990s. In 1988, Chaykin created perhaps his most controversial title: Black Kiss, a 12-issue series published by Vortex Comics which contained his most explicit depictions of sex and violence yet. Telling the story of sex-obsessed vampires in Hollywood, Black Kiss pushed the boundaries of what could be shown in mainstream comics.

This was another radical revamp of DC charactersthis time, DCs science fiction heroes from the 1950s and 1960s, such as Tommy Tomorrow and Space Cabby. He collaborated twice with artist Mike Mignola. This was followed with the Ironwolf: Fires of the Revolution graphic novel in 1992. [26] Chaykin then co-created/designed Firearm for Malibu Comics in 1993.This was followed by the four-issue miniseries Power and Glory in 1994, a superhero-themed PR satire for Malibu Comics' creator-owned Bravura imprint. In 1996, DCs Helix imprint published Cyberella, a cyberpunk dystopia written by Chaykin and drawn by Don Cameron.

Chaykin began to drift out of comics by the mid-1990s. With the exception of several Elseworlds stories he wrote for DC Comics, including Batman: Dark Allegiances which he wrote and drew in 1996, his comic output became minimal as he became more involved in film and television work. He was executive script consultant for The Flash television series on CBS, [27] and later worked on action-adventure programs such as Viper, Earth: Final Conflict and Mutant X. Near the end of the decade, Chaykin started to drift back into comics and co-wrote with David Tischman the three-issue mini-series Pulp Fantastic for the Vertigo imprint of DC, with art by Rick Burchett.